“Your ideal body is probably bigger than you think”

I wrote this on Instagram the other week and it fostered a LOT of conversation. Our conditioned response is to assume that a bigger body is automatically less healthy. Whereas if we flip the script, a body that carries more energy and power is closer to an ideal body situation. Let’s explore…

The reduction in body size is lauded, from the dizzying heights of our government to the comments of our next door neighbour as she leaves for (ugh I don’t even want to type it) Slimming World, as being desirable and healthy. The phrase “weight loss” has almost a Pavlovian response in our brain as being attention grabbing, intriguing and rewarding. We see the phrase and wonder “is there something new I need to know about losing weight?”

We’re told we should have a smaller body because that is healthy.

The reality of the matter is, though, that a human body isn’t automatically healthier the smaller it gets, and in pursuit of weight loss alone, without any effort to build our bodies, we’re making ourselves less metabolically healthy, and less looking like we want to look by losing weight.

A healthy amount of muscle mass and body fat is a corrective force to a lot of the health issues that are currently attributed to the much vaguer “body weight.” It’s basically the answer to the so-called “obesity paradox” where doctors have been mystified by the way people of higher body weights can still be in decent physical condition and have a higher survivability rate.

But this doesn’t tie in with the implication of the blanket approval of weight loss rhetoric of “the smaller the human, the healthier the human”. Because behaviours that lead to consuming less food and maintaining less muscle and bone density than a body naturally needs (which equals a smaller number on the scales) = low energy turnover, body tissues with less stored nutrients, a reduced metabolic rate, a weaker body overall and with lower reserves for survivability should they become ill or injured.

The behaviours that lead to a smaller body are the same as those that lead to a weaker body: less energy than we need and less structural integrity to our body parts (a weaker body).

Just reading that makes sense, doesn’t it?

And notice I said “behaviours” and “[less] than a body naturally needs”. A body that is naturally light isn’t automatically less healthy, just like a body that is naturally big isn’t automatically less healthy.

The obesity paradox suggests that (by definition of the inherently racist, and made-up, BMI labels, which I’ll let other, more clever people go into the problems with) obese people with chronic illnesses lived longer than those with a normal weight. That link will explain it more eloquently than I do.

This doesn’t simply mean that more body mass = longer life. Just like smaller body mass does not = longer life.

But it does shine a torch on how unhelpful body weight and size alone are as measures of health. A human will be bigger and heavier when it has more muscle, for example, and a higher muscle mass is a protective force against metabolic and cardiovascular disease.

However.

This goes against the powerful interests of a multibillion pound industry.

The diet industry is worth over £2 billion in the UK alone. Not only the diet industry, but also the pharmaceutical industry – demonstrated by the terrifying emergence of diabetes drugs sold as weight loss drugs, benefits from the inferred assumption that if fat bodies are unhealthy, then surely any body fat is symptomatic of a problem being present. If there was worldwide government hand-wringing, medications and membership clubs devoted to minimising fingernail length, we’d all be bloody terrified of our fingernails growing.

Humongous fingernails are problematic, sure. As are body fat percentages at the extreme end of the scales (high and low).

It’s a clunky incomplete metaphor, but pathologizing of bigger bodies is really no different if we think of it like this.

Weight loss as a health solution is highly overrated. But worst thing about nearly every weight-loss workout or diet is that they more often than not don’t protect our lean body mass. This leaves the dieter in a worse place than they were to begin with; less muscle mass to make their body and metabolism work normally, and a harder to maintain lower body weight because of that.

We’ve internalised the implication that lower weight correlates with increased health to the extent that it’s easy to assume that everyone would benefit from losing weight, as if it is a healthy behaviour in itself, just like how everyone would benefit from wearing sunscreen.

You can read more about this here.

But now we come to: what if you feel fat and unhealthy and not attractive. Regardless of what I’ve said so far. What if you still want to lose weight. What if you think that your ideal body is smaller. I totally understand why you feel this way.

We’re surrounded by images of health and beauty looking toned and small; surely, our bodies that don’t look the same as them can’t also be just as healthy and beautiful as them? This doesn’t add up in our heads. And I know exactly what that feels like; I’ve been there.

At the budding phase of my eating disorder as a teen, and throughout the years when I was “better” in everyone’s eyes but still couldn’t get through a day without eating (weirdly) and exercising (compulsively) being a noisy distraction, I had this exact problem: I didn’t like how my body looked and more importantly felt like I had no control over it. I ate so strictly but still didn’t feel small enough, that I couldn’t fathom how other people seemed to be able to eat “normally” without their bodies changing weight day to day, I felt like I was only one relaxed slice of cake without any compensations in the gym or for my next meal away from a whole new layer of bodyweight.

Even when I was at my lowest weight, I wasn’t at a low enough weight for it to be treated as an illness by a doctor. If they’d have looked closer though… It was a low enough weight for me to be cold all the time, faint frequently, have to lie down a lot, barely sleep and have had no period for over a year. Yet maybe my height meant that on the all-important body mass index chart I didn’t show up yet as being “ill”, when I clearly was and was forced to spend literally years digging myself out of the hole caused by the glorification of weight loss, especially as a girl.

I did not feel good about myself the less I weighed—I didn’t feel good at all. It caused me huge anxiety because once I’d lost weight, the stress I felt about keeping it off was all-consuming. And I still didn’t like my body. I was scared of it. It felt alien and out of control. It was a battleground. The entire missing piece from my understanding was a positive and constructive relationship with how I used it, disconnected from how it looked and what it weighed.

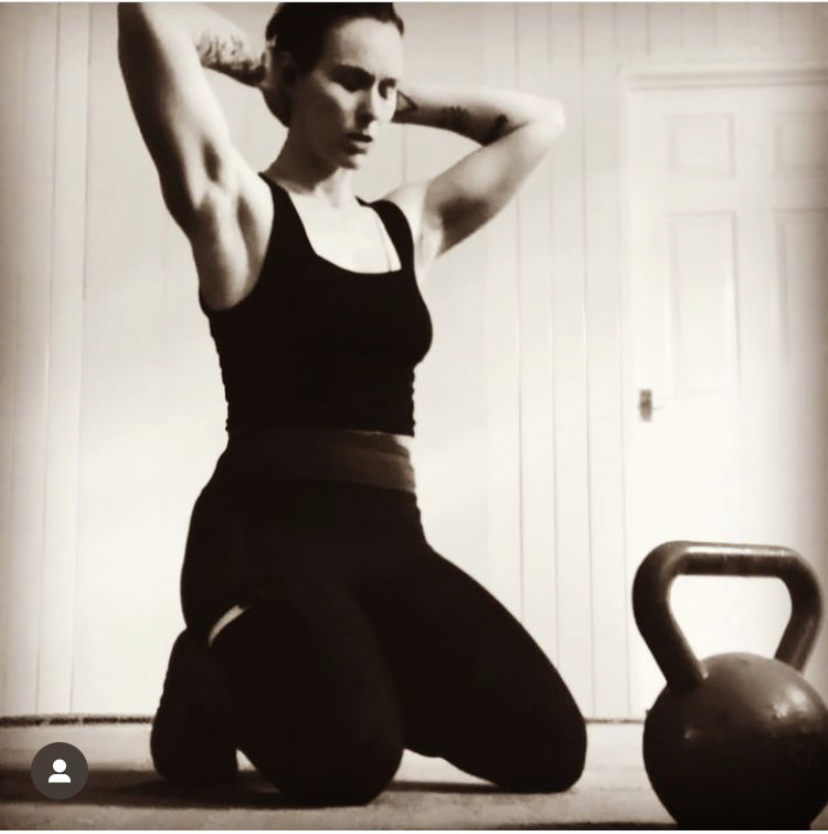

Lifting weights was the gateway into realising that actually, building and maintaining my body’s structure was a normal and empowering pursuit, where weight loss was not.

I love the term “body positivity” because I love bodies. I love learning about how they work and what they allow us to experience. I love that we exist at all. But there’s a lot of resistance to that phrase generally, because it’s a huge gap to bridge for someone to come deep from the weeds of actively disliking their body to “loving” it. It’s too far. “Body neutrality” is a more useful phrase. Neutrality doesn’t mean “not caring”, instead it means being effortlessly habitually physically active and effortlessly habitually an eater of enough to cover your bodies nutritional needs, without any emotion, other than curiosity and satisfaction, underlying the physical activity and eating experiences, and without the way your body looks (and the way you eat and exercise), consuming your identity.

The behaviours that lead to a healthier body aren’t the same as leading to a smaller body

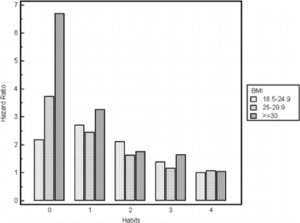

The pursuit of body perfection, or any aesthetic focus over legitimate health focus, will come at the expense of body neutrality. We have to accept that trade-off. But as we now know, the more healthful lifestyle habits you engage in, the lower our hazard risk, regardless of BMI.

Hazard ratio for all-cause mortality by body mass index (kg/m2) and number of healthy habits (ie, fruits and vegetable intake, tobacco, exercise, alcohol).

I now weigh, on average, several kgs more than I did when I felt too big, but I feel completely differently about it because my body size has come from a deliberate effort to be strong. The experience of muscle growth happening to me was mildly surprising at first. But it felt… powerful. Intentional. It taught me that I could grow, and that I needed to care for myself and do hard things to make it happen. The way I felt about the hard-won muscle I gained from strength training plugged the gaps in my body image. I see this happen over and over again in the women I train.

I also have to eat a lot more food than I thought was acceptable for an adult woman* to maintain what I can do with my heavy weights.

*do you remember the time you learned that to be an adult woman meant that you constantly had to be vigilant about eating as minimally as possible to get by?

I no longer care about being lean more than I care about enjoying the flexibility in the kind of eating habits that come with a body bigger than I thought I should have. I have the kind of eating habits that I was taught that an adult woman shouldn’t aspire to. I love salads, but I don’t smile at them like all the women in google images of woman eating salad do.

Learning the positive feedback loop of building strength, and learning to accept that being stronger means that my body weight will change slightly all the time depending on factors to do with how well I sleep, eat and reduce stress so that I can train to be strong, has allowed me to enjoy my life, without body/food preoccupations.

It has disengaged exercise from currency for eating, so that I can enjoy it. And I’ve seen this in so many other women who “hate exercise”; they do, until they realise that they can do it for the pleasure of how it makes them feel, not because of an obligation to burn off the food they ate.

It can take a while to get to this point, though. There is a time when training becomes a self-reinforcing process, where the more you do it, the better you get at it, the more you enjoy it, the more you want to do it, etc.

What I want for you all is a more loving, more generous, and more expansive goal for your body than the “losing weight” one that the world keeps trying to hand us. If you feel like you could feel better in your body, that doesn’t have to be tied to being smaller.

Here are your key points:

- Health behaviours matter more than your weight – exercise most days, eat fruit and vegetables and protein and carbs and fats, drink loads of water, don’t smoke (does anyone still??), minimise alcohol (the less you drink the less you need, ask me how I know!)

- More muscle and higher bone density will lead to a heavier body. This is not a bad thing.

- Body fat is not abnormal and not pointless, and it comes with having a healthy body.

- BMI is made up.

- Strength training liberates women.

This incudes you, my friend.